Turbulence

Topics available on this page:

- Turbulence

- Mechanical turbulence

- Turbulence mat

- Accidents and incidents

- Thermal turbulence

- Clear Air Turbulence - CAT

- Intensity of turbulence

- Hazard mitigation

- Accidents and incidents

Turbulence

Turbulence is the irregular movement of the air flow that can cause ascending and descending shakes on an aircraft in flight.

Turbulence can be classified into three types: mechanical turbulence, turbulence mat and thermal turbulence.

Mechanical turbulence

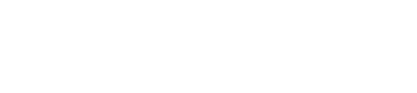

The mechanical turbulence is caused by the wind flow through a solid structure (mountain, buildings, airport hangars, hills etc.).

Source: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak/media/14_phak_ch12.pdf

Source: https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_00-6B.pdf

In plateau regions, relief can contribute to the occurrence of "mountain circulation" that can trigger deep convection processes and generate orographic turbulence.

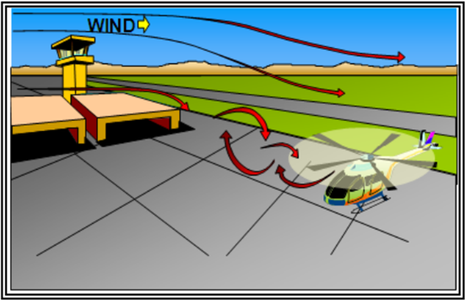

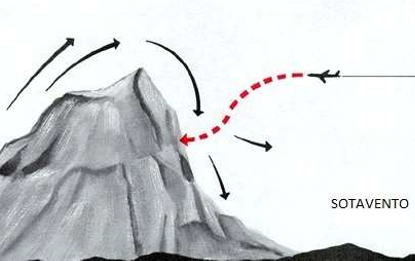

Orographic turbulence arises from the friction of the air when blowing against mountainous elevations, that is, it is a form of mechanical turbulence.

The intensity of this phenomenon depends very much on the direction and magnitude of the wind, the roughness of the terrain, the height of the obstacle and the stability of the air. The more perpendicular to the wind barrier, the more pronounced the effects will be. Likewise, the greater the magnitude of the wind, the stronger its leeward effects.

The strong winds cause the effects of turbulence to be kept at a greater distance.

Note 2-1

For an aircraft to avoid the effects of mountain turbulence, it is recommended to cross the barrier at a height of 2.5 times the mountain elevation. For example: A mountain that measures 1,000 meters of height would have to be crossed to some 2,500 meters of height.

In the windward clouds, the airplanes must find elevation of altitude (gain of sustentation) and, to leeward, loss of altitude.

A windward of the mountain the air is forced to rise, while the leeward, descends and extends its effect down on the valley, in the form of waves that can propagate by several kilometers, being the waves nearest to the mountain the more turbulent.

Although they are more intense with the highest altitude, orographic waves can occur in any range of mountainous terrain or succession of crests at least 300 feet or more in height.

The turbulence generated by an orographic wave can be as intense as that caused by a thunderstorm.

In experiments, accelerations from 2G to 4G were found in violent air currents, both horizontally and vertically, and on one occasion the 7G was exceeded, varying from 2,000 to 3,000 feet per minute.

Turbulence mat

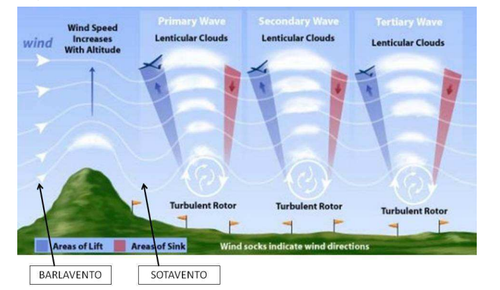

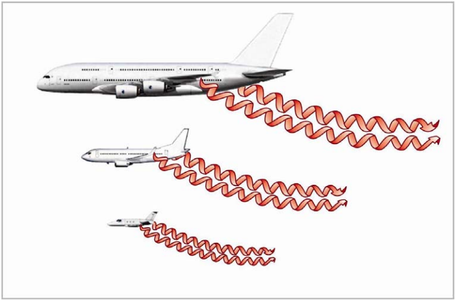

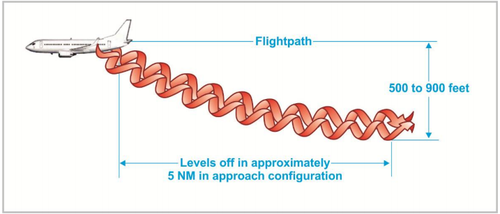

Also called Wake Vortex Turbulence. This is an atmospheric disturbance caused by the passage of an aircraft in flight or during landing and take-off procedures, when intense swirls and vortices, which can reach 300 km/h, are produced at the tip of the aircraft wing.

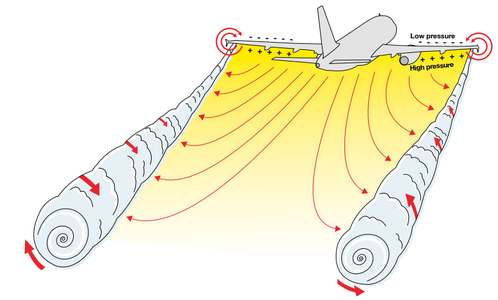

The flow of air passing under the wing of an aircraft is conducted around the tip of the wing to the region above the wing, through the larger pressure difference below the wing and smaller above the wing, thus creating a trail of turbulence mats .

Source: Skybrary

Source: Wake Vortices , C. Lelaie, Airbus Safety First Magazine No. 21, pp. 42-50 , January 2016

The force of the vortex is determined by the weight, velocity and shape of the wing of the generating aircraft.

Source: FAA AC 90-23G - Aircraft Wake Turbulence

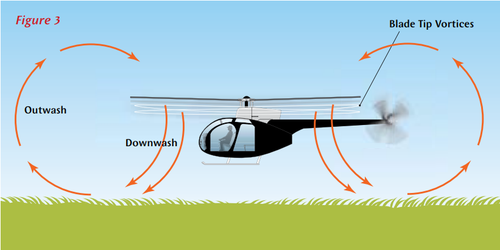

When operating at lower speeds (20-50 knots), helicopters can also cause turbulence mats. Depending on the size of the helicopter, the turbulence mat generated by them may have similar force to the mat generated by fixed wing aircraft of similar weight. Most accidents involving helicopters and small planes occur when small aircraft are taking off or landing while helicopters are hovering near the runway or flying in the circuit. The turbulence mat generated by helicopters varies according to the maneuvers that are performed in flight.

Source: New Zealand Air Force Good Aviation Practice Booklet on Wake Turbulence

Source: New Zealand Air Force Good Aviation Practice Booklet on Wake Turbulence

The vortexes of the turbulence mat generated by airplanes usually persist between one and three minutes after the passage of the aircraft depending on the conditions of air stability and wind speed.

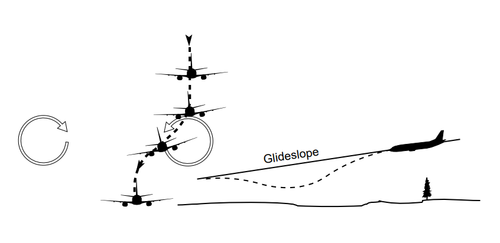

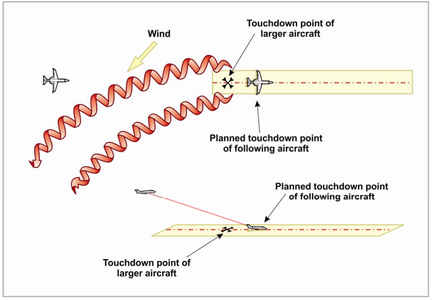

This air disturbance can be potentially dangerous in congested airspaces when aircraft follow the same trails - that is, they are "in trail", flying close to each other. This situation is mainly found near the ground, in the vicinity of airports, where the aircraft are approaching or departing.

The three basic effects of the turbulence conveyor on the aircraft are: violent swing, height loss or ascensional speed and structure efforts. The greatest danger is the violent swing of the aircraft that penetrates the conveyor to a point that exceeds its command ability to withstand this effect. If the encounter with the vortex occurs in the approach area, its effect will be greater because the aircraft that follows is in a critical situation with respect to speed, thrust, altitude and reaction time.

Source: FAA - Pilot and Air Traffic Controller Guide to Wake Turbulence

If a turbo-generator aircraft is rising or falling rapidly, the vortices generated may persist at various flight levels.

Source: FAA AC 90-23G - Aircraft Wake Turbulence

At cruising altitudes, the vortices extend longer because of the lower air density. The dissipation becomes even more difficult when the prevailing wind speed is low. Because of this, it is important to observe the ATC separation minima.

The turbulence belt separation minima are based on the grouping of aircraft types into categories, according to the maximum certificated take-off weight.

See items 3.23, 3.24, 3.25, 5.12.3, 6.6, 6.7.1.6, 10.13.4, 10.17.3.5 of ICA 100-37 - Air Traffic Services and ICA items 4.2.3.1, 4.3.2 100-12 - Rules of the Air.

- Access the ICA 100-37

- Access the ICA 100-12

Even when the responsibility of avoiding turbulence mat is the pilot in command, the aerodrome controllers inform, as far as possible, the aircraft about the expected occurrence of turbulence mat. However, the occurrence of hazards associated with the turbulence belt can not be accurately predicted and aerodrome controllers can not assume responsibility for always issuing warnings about such hazards or their accuracy.

Note 2-8

In order to mitigate the danger of turbulence, it is essential that the pilot maintain situational awareness by monitoring other transits (aircraft) in the vicinity, listen to the frequency and use the TCAS Display.

In congested airspaces, it may not be appropriate to ask the ATC for details about the aircraft ahead because of the risk of obstructing the frequency with unnecessary calls. In this case, it is possible to estimate the turbulence conveyor category of the aircraft that is ahead through the knowledge of the other air carrier's fleet.

Note 2-9

If you find a turbulence mat during any flight phase, it is recommended not to apply sudden movements on the ailerons, rudder and elevator. This measure is intended to avoid the wear and tear of the structure of the aircraft or the breaking of the cables connecting the various control surfaces.

At low levels or at ground level, the vortex dissipation of the turbulence mat will occur more rapidly. Abrupt changes in wind direction or occurrence of crosswinds may contribute to facilitating the dissipation of the turbulence mat at these levels or diverting them from the runway axis.

Source: FAA AC 90-23G - Aircraft Wake Turbulence

Although ground vortex dissipation of the turbulence belt occurs more rapidly, when issuing authorizations or instructions, air traffic controllers consider the hazards caused by the exhaust of jet engines and rotor blasting, in the case of are taking off or landing, particularly when intersecting tracks are being used.

Jet engine exhaust and rotor blast can produce localized wind speeds with sufficient intensity to cause damage to other aircraft, vehicles and personnel circulating within the affected area.

Accidents and incidents

The turbulence mat was mentioned in the investigation reports of the following accidents / incidents:

- A319 / B744, en-route near Oroville WA USA, 2008

- A320, en-route, North East Spain 2006

- A306, vicinity JFK New York USA, 2001

- B733, en-route, Santa Barbara CA USA, 1999

- B735, en-route, North East of London UK, 1996

- C185, Wellington New Zealand, 1997

- E170, en-route, Ishioka Japan, 2014

- P28A / S76, Humberside UK 2009

- WW24, vicinity John Wayne Airport Santa Ana CA USA, 1993

See more about the danger caused by the turbulence mat at: https://www.bfu-web.de/EN/Service/V180-Video-EN/V180-Video-EN_node.html

Thermal turbulence

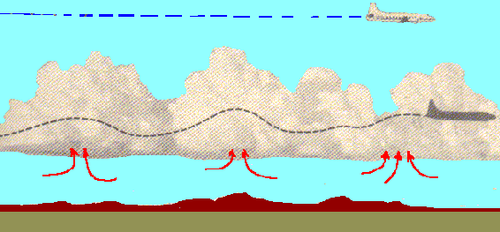

Thermal turbulence is caused by vertical convective air currents arising from the differential heating of the soil and the air layer above it. The transport or advection of cold air on the hottest soil can also generate vertical convective air currents.

Note 2-2:

For flights at low altitude, in regions with high temperature, there is possibility of turbulence.

Although it is typically of light classification, this type of turbulence can present with moderate intensity in arid places due to the strong displacement of the mass of air in diverse directions and speeds, being able to cause the aircraft to undergo the effects of the horizontal and vertical speed variation to the through this irregular airflow.

The descending currents cause the aircraft to be deflected down its normal trajectory, which may cause a touch on the runway before the desired point (undershoot).

The upward currents force the aircraft up its normal landing path, resulting in a touch beyond the desired point (overrun).

Clear Air Turbulence - CAT

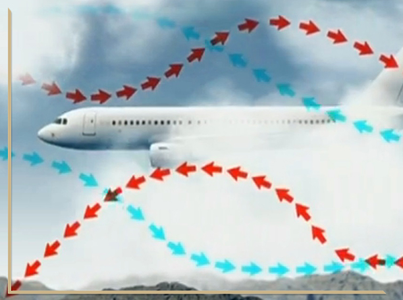

But turbulence can also affect en-route flights. This phenomenon is not always associated with rainfall and normally occurs above 20,000 feet. It's called "clear air turbulence" (in English, Clear Air Turbulence - CAT), originated by jet stream ( jet stream ) and commonly reaches the aircraft in cruise flight at about 30,000 feet. This type of turbulence originates from a strong shear of the wind, that is, great variation of the speed in a few kilometers.

CAT events are reported through reports of aircraft that were in the region of turbulence and passed on to SIGWX charts.

However, the charts do not always present a good index of prediction of the occurrence of a CAT, because it is a phenomenon of microscale and that presents abrupt changes in its behavior and its characteristics, being able to disperse in a fast spatial scale.

There are technologies under development for the detection of CAT that are being tested and improved by NASA, scientific institutions and airlines, such as Delta Airlines.

The E-TURB Radar (Enhanced Turbulence Radar) is a meteorological radar developed by NASA that uses turbulence detection algorithms built into its operating dynamics. The algorithms detect deviations of Doppler velocities using scans of multiple radar antennas, computing the response of anticipation to the encounter of the phenomenon and generating a real time display of the locality and the intensity of the phenomenon through different types of colors.

TAPS (Turbulence Automatic PIREPS System) is an automatic turbulence reporting system derived from E-Turb Radar technology. The system automatically sends turbulence reports to nearby operations centers and aircraft. Automatic information is based on accelerations and fluctuations that impact aircraft from the thresholds of turbulence detection algorithms.

US airline Delta Airlines has launched an application called Flight Weather Viewer that provides turbulence area graphics and real-time forecasts for pilots. The company's aircraft avionics sensor system uses special turbulence algorithms combining vertical accelerometer data with weather data such as tilt, rotation and wind speed, thus producing turbulence reports. These reports are automatically sent to weather forecast models and made available in real time in the application.

Turbulence threat alert en-route can be sent by company pilots in the form of audio and visual notifications, signaling when and where the belt tightening warning should be turned on and when pilots need to be in charge. This application is customized by aircraft type, interpreting that an aircraft 737 and another of type 767 have different impacts on turbulence due to difference in size and weight.

Intensity of turbulence

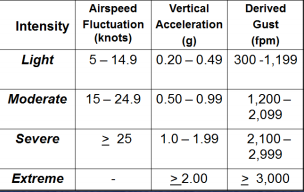

According to the UK Met Office Handbook of Aviation Meteorology and WMO, turbulence is categorized as mild, moderate or severe:

- Light turbulence : Aircraft speed fluctuations occur in the order of 2.6 to 8 m / s (5 to 14.9 kts) with gust velocities in the range of 1.5 to 6 m / s (5 to 20 ft / second) . Passengers may be required to wear seat belts, but loose objects inside the aircraft remain at rest. They are the most common types found, causing small oscillations and gentle bumps.

- Moderate turbulence : Aircraft velocity fluctuations occur in the order of 8 to 13 m / s (15 to 24.9 kts), with gust velocities in the range of 6 to 11 m / s (20 to 35 ft / second) lasting approximately 11 minutes. The use of safety belts is undoubtedly mandatory, loose objects move and the movement by the aircraft becomes difficult.

- Severe turbulence: Aircraft velocity fluctuations equal or greater than 13 m / s (25 kts) occur at gust velocities of 35 to 50 ft / sec (11 to 30 m / s) lasting approximately 7 minutes. There may be momentary loss of control of the aircraft and occurrence of structural damage. Passengers can be thrown violently out of their seats and suffer serious injuries due to collision with loose objects inside the aircraft.

Figure - Parameters of the quantitative measures of turbulence analysis assimilated by on-board computers in modern aircraft. Source: National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

The quantitative measures of turbulence consider speed fluctuations (defined as the maximum speed variation from the indicated flying speed under turbulent conditions), the derived bursts (defined as the estimated velocity of a given vertical gust of wind impacting flight altitude due to the impact of a vertical gust of wind on the aircraft) and vertical acceleration (defined as the standard gravity acceleration deviation peak of 1.0 g measured at center of gravity of the aircraft).

The effect of turbulence on the aircraft also depends on variables such as differences in adjacent wind speed, aircraft size, aircraft weight, wing surface, and flight altitude.

Note 2-3:

The higher the aircraft speed, the greater the effect of in-flight turbulence. In aircraft with a very large wing surface, a greater effect of turbulence can be expected.

Prior knowledge of the turbulence areas helps to avoid or minimize the discomfort and hazards caused by this phenomenon, creating the possibility of making a detour on the route.

Mitigation of Danger

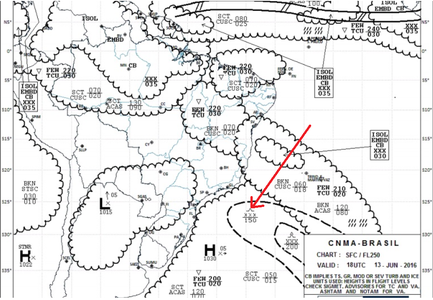

SIGWX cards may contain indications of areas of turbulence.

Click on the image to enlarge.

Source: www.redemet.aer.mil.br

The symbol highlighted by the red arrow on the SIGWX chart above represents moderate turbulence prediction.

Usually the turbulence and its intensity are reported by the pilots in the phony and the flight controllers pass the information to the other pilots that approach the region where it was reported.

This information serves to alert and prevent aircraft coming or en route with the phenomenon.

The reports evaluate a turbulence event, the reaction inside and outside the aircraft and the information of locality, time (UTC), intensity, altitude, duration and type of aircraft.

It is important to emphasize that the pilot's qualitative evaluation of the turbulence event has a high degree of subjectivity, as it will depend on the experience and sensitivity of the pilot in relation to the turbulence. This sensitivity can be influenced by aircraft type, flight altitude and flight speed.

A turbulence event can be reported as being of light intensity by a Boeing 737 pilot who has little knowledge and sensitivity to the situation. The same event can be reported as being of severe intensity by a pilot of a smaller aircraft, such as Cessna 172.

Note 2-7

When reporting a turbulence event, it is important to be aware of the subjectivity aspect of the report in the face of the actual situation, avoiding over reporting the turbulence intensity to a greater or lesser extent.

One way to reduce the degree of subjectivity of turbulence reporting is to add information about the aircraft type, altitude, and flight speed.

Note 2-4

If it is impossible to deviate from the turbulence area, the following precautions are generally recommended to minimize the effects of this phenomenon:

a) correct the indicated speed of the aircraft to smooth the effects of the turbulence, according to the standards of the apparatus;

b) avoid low altitude flights between mountains, especially near the leeward side of one of them;

c) avoid "roll" clouds, as they constitute areas of intense turbulence;

d) avoid lenticular clouds, especially if their edges are ragged;

e) do not rely excessively on altimeter indications near mountain peaks, as they may contain errors greater than 1,000 feet;

f) to perform the landing approach at a speed slightly above the expected speed in order to avoid a sudden drop in lift;

g) be aware of the possible psychological effects of turbulence on the crew.

Note 2-5

In the case of overflight of a mountainous region with strong surface winds, when faced with a severe turbulence condition, the pilot must request Air Traffic Control to move to a higher flight level, where he will probably find better conditions.

Note 2-6

Considering the direction of the wind, it may be potentially dangerous to fly from the side of the leeward of hills and slopes, for in this region turbulences due to descending wind currents are normally expected due to the existence of the natural obstacle.

Access the RBAC 135

In the flight planning phase, the occurrence of turbulence at the starting aerodrome, along the route or at the destination aerodrome can be identified by consulting weather reports.

Satellite images, weather radar images and significant time charts (SIGWX) help in identifying this phenomenon.

They may indicate potential regions of turbulence:

- In satellite images: the existence of nuclei and regions of convective activity as dense cloud formations, storms, instability lines and frontal systems in the flight path.

- In the meteorological radar images: the presence of convective clouds in the vicinity of the departure, destination and alternative airports.

- In SIGWX charts: regions where storm clouds, instability lines and frontal systems are encountered. The charts also present the positioning of the jet streams in Brazil, and consequently localities containing areas of clear sky turbulence.

Accidents and incidents

The turbulence was mentioned in the investigation reports of the following accidents / incidents:

- IG-094 / CENIPA / 2014

- A - 207 / CENIPA / 2013

- A-009 / CENIPA / 2012

- A-032 / CENIPA / 2011

- A-011 / CENIPA / 2011

- A-066 / CENIPA / 2011

- A-082 / CENIPA / 2010

CENIPA reports available at http: // prevca # mce_temp_url # o.potter.net.br/relatorio/page/1

- E145, en-route, near London ON Canada, 2014

- A388, en-route, southeast of Mumbai India, 2014

- B772, en-route, Northern Kanto Japan, 2014

- A346, en route, eastern Indian Ocean, 2013

- A332, en-route, near Dar es Salaam Tanzania, 2012

- B732, vicinity Islamabad Pakistan, 2012

- A343, en-route, mid North Atlantic Ocean, 2011

- B773, en-route, South China Sea Vietnam 2011

- B773, en-route, Bay of Bengal, 2011

- A333, en-route, Kota Kinabalu Malaysia, 2009

- DHC2, Squaw Lake Quebec Canada, 2005

- A321, en-route, Vienna Austria, 2003

- B741, en-route, Pacific Ocean, 1997

*As notas que contém itens de regulamentos brasileiros não foram traduzidas para que a interpretação delas não seja diferente da interpretação pretendida.

**Notes containing items of Brazilian regulations have not been translated so that their interpretation is not different from the intended interpretation.

Did you find errors in this content ? Send email to meteorologia@anac.gov.br to report.